It doesn’t seem like long ago that I was writing with excitement about taking up a role on the SLA Board of Directors. Today, I’m writing with regret about stepping down.

It doesn’t seem long ago because it isn’t, really. I’ve served two years of a three year term, and stepping down a year early sticks in my throat and hurts and feels an awful lot like failure.

But it also feels like a new beginning, because it is. I’m pregnant, and we’re expecting our second child in the spring. I’m extremely excited and unbearably nervous: a baby took up all my time and effort, and a toddler takes up all my time and effort, so what on earth are you supposed to do with a baby and toddler at once?

Cope, of course. Because coping is what we do. But there comes a point when you have to admit that you can’t cope with everything, not all at once, and – what’s even harder – admit to yourself that there is no shame in this.

I haven’t quite got the hang of that second bit, yet. Because I am still ashamed. I know that I have made the right decision, to step down from the SLA Board. Those of you in SLA will know that it’s a challenging time for the association, full of great change, and a time when they particularly need leaders who can give their full and best effort and attention to SLA. I won’t be able to.

I could cope. I could stay on and do the minimum. I could put aside time for Board calls and delegate bedtimes and then get called away and have to go, because when your baby has vomited more milk than you realised could fit in their stomach all over themselves and their cot and is now cold, wet, and hungry again, you don’t wait until someone proposes an adjournment. I could agree to take on the extra work of leading implementation teams and taskforces, with the best of intentions. I could put undue pressure on my Board and association colleagues when they have to pick up the slack, because I can’t do it all.

And SLA doesn’t need me, specifically. No-one is going to cry themselves rigid because I’m not on a conference call, or run towards me at conference shouting ‘Bethan! Beeeettthhaaann!’ and then cling to my leg and refuse to let go. SLA needs good people, and it has them, on its Board and its staff and in its membership. I have every confidence that Karen Reczek (who will take up the empty Board seat in January) will serve SLA at least as well as I could have, and very probably much better.

But it’s not just about the pull between parenthood and professional involvement. I am absolutely not saying ‘I have kids, so I can’t do this.’ It’s about things that happen in your life, and knowing that when some things come in, other things have to be let go. It’s certainly not unique to having children: your life can be equally changed by illness, grief, by caring for others or yourself, by moving house or falling in love. Things happen. Things change. And you have to change with them or you risk falling apart.

While my priorities have changed, it’s not that I don’t care anymore, but my time is full, and, more importantly, my brain is full. I work on four services/projects at work now, and I have multiple SLA responsibilites, and a CILIP Chartership mentee, and family and friends and a home and a half-written probably-abandoned nanowrimoproject and so many books to read and… I care about all of these things. They all enrich my life. I want to do them all. But I can’t. I’m already finding that I’m making mistakes, underperforming not just for SLA but at work and at home. They may not be big omissions or errors (I forgot to put the bins out this week), but they’re there, and they matter. An email I forgot to send has hurt someone, and that failure is going to stay with me for a long time.

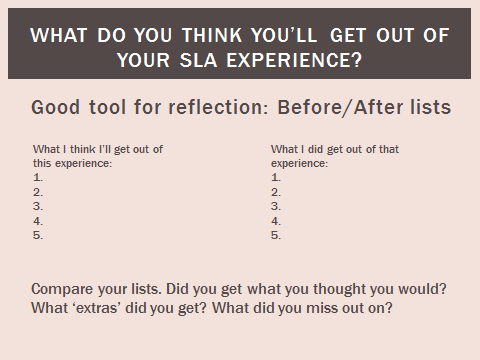

[Please don’t think that I’m putting all of this down to SLA vs Life. I have a list of ‘things that I cannot possibly do all of and stay sane’. It includes (but is absolutely not limited to):

- Be brilliant at my job

- Be an amazing mother

- Cook delicious and healthy food

- Keep a beautifully clean and tidy house

- Be top of my fitbit friends league chart

- Be professionally involved and up-to-date with everything in the library, archive & HE sectors

- Learn to do something really cool, like crafting maybe? Or become an expert in something interesting to talk to people about at parties. That I don’t go to. But I’d be really fascinating if I did.

Most days? I don’t even manage one of these.]

So if stepping down is the right thing to do, why the guilt? Why the shame? Because, of course, I feel like I should be able to do it all. I feel – don’t laugh, please – that I’m letting feminism down by stepping back from a professional post because of domestic concerns. I compare myself with people who I know are hugely overworked, and who I tell that they should do less and take breaks because they need time for self-care if they’re not going to burn out – and I think ‘but they can do it, so I should be able to!’. I compare myself to Victorian working-class women, the kind of people you find in Elizabeth Gaskell’s novels – you know, 12 hours in the factory then home to look after seven kids, one of them a cripple, while making beautiful lace to sell and teaching themselves natural history. I am fully aware of what a ridiculous person this makes me.

Of course, that isn’t all of it. There’s the fear of laziness, too. The voice that tells me that I should be working all the time, that time spent on things for my recreation and relaxation is wasted, unjustifiably self-indulgent. Pregnancy actually makes this one a bit easier (‘but baby needs me to sit on the settee with a stack of biscuits and a Margery Allingham!’), but although I do my best to remind myself that my physical and mental heal and weal are not luxuries, it’s a constant battle to make it stick. I am trying to teach myself this: you do not have to come last.

And: you do not have to be defined by your duties. And: do not be ashamed of joy, of seeking it and making the most of it.

Recent Comments